What are active recovery activities?

Activities for an active recovery day are those that activate your parasympathetic nervous system: the rest and recovery branch of your nervous system.

That means activities that:

- Are low intensity

- Are low impact

- Include varied and wide-ranging movement patterns

- Mildly increase heart rate

ome more common examples of activities are:

- yoga or pilates

- swimming

- an easy swim or bike ride

- a post-dinner walk

- gentle hiking, through the urban sidewalks or countryside

- playing frisbee with your dog

- soft tissue work like foam rolling or massage

- connecting with friends and family, laughing, and playing

- anything else that gets you moving and brings some joy to your day

Whatever activity you choose, the purpose of an active recovery day is to not increase workout capacity.

In other words, don’t push harder or longer relative to what you’ve been doing in workouts over the last two weeks.

How do you know if you need a recovery day (or more)?

If you’re generally following your workout program’s schedule of weekly workouts, you’ll be working out about 3-5 days per week. On a typical week, you’ll have about 50% active training days, and 50% active recovery days.

The starting guideline for balancing training stress and recovery is to start by taking at least 1 active recovery day after every challenging workout day.

Those are general guidelines. If you’d like to make your program more personalized to you and your specific lifestyle and goals, listen to your body.

Every individual’s body is unique: they’ll feel stress differently and recover from stress at different rates. Ultimately, only you can know your unique stress and recovery signals. Those are the signs that tell you when you can push harder and when it’s smarter to do less.

Soreness check

When you’re moving your body in new ways and with increased loads, your muscles will feel sore in the 1-3 days following your workout. That’s normal and expected.

You can continue to strength train during moderate muscle soreness.

Pay attention to your patterns of muscle soreness.

As your body becomes more accustomed to moving and lifting, the duration and intensity of the soreness should decrease. Your body is making deep structural adaptations, and you’re getting fitter. Solid.

Below are some more common key body signals that guide whether you need more or less recovery.

Fatigue can be felt both physically and psychologically.

Fatigue feels like:

- “Heavy” movement (e.g., feeling physically weighted-down, with a body that feels harder to move. Walking or running might feel like slogging through mud rather than snappy and weightless.)

- Difficulty maintaining strong posture and form

- Brain fog or slow thinking

- Uncertainty and indecisiveness (difficulty making decisions or deciding what to do next)

- Slow and delayed movement (rather than quick and snappy movement)

- Feeling tired, depressed energy, and or depressed mood

- A vague sensation of feeling “off”, or somehow not quite right

- Disrupted sleep

- More intense cravings, especially for refined carbs (sugar and sweets) or high-fat foods

- Decreased sex drive

- Getting sick often, or illness that lingers

To contrast, being fully recovered without fatigue feels like:

- being mentally clear and alert

- feeling energy and motivation to move

- feeling “on”, and banging on all cylinders

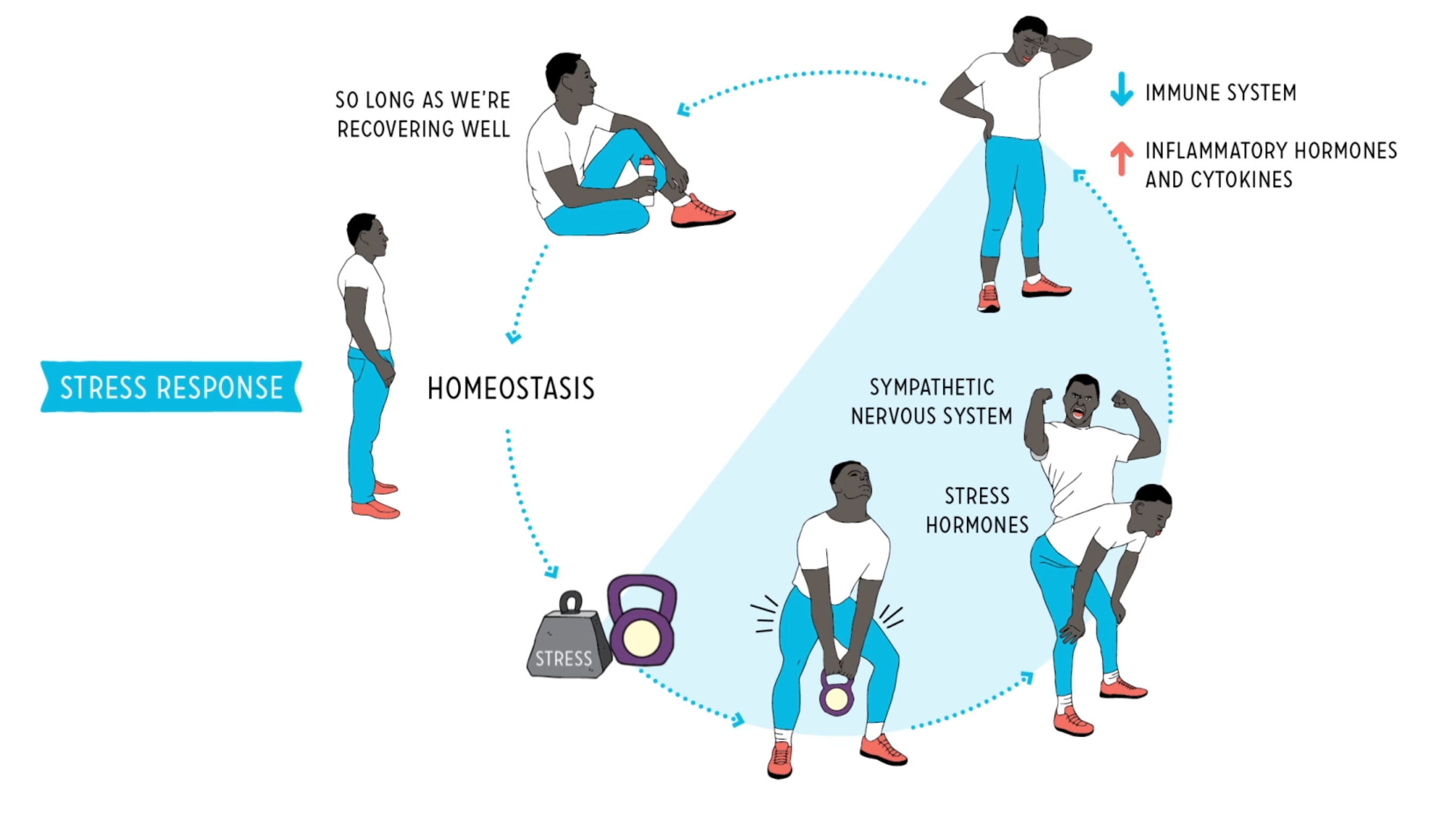

Remember that all stress is cumulative.

If you’ve had greater stress in other areas of your life recently (other than physically working out), your need for total recovery will be affected.

Regardless of the source of stress, all stressors act on the same central nervous system and brain. That same brain creates your experience of either stress and fatigue or recovery and vitality.

No matter the source of stress, responding to stress with adequate recovery is necessary to make you physically, mentally, and emotionally stronger.

Why does recovery matter?

The purpose of active recovery is to support your body’s natural processes of growth.

Recovery is a necessary and fundamental part of getting stronger.

For example, you’ve just done a challenging workout.

You’ve put in effort. You know you’ve put in effort because your heart beat faster, your muscles tensed, your joints moved and tissues stretched.

That means you’ve done your part in starting muscle breakdown. Now starts a muscle recovery phase. This is the phase where strength is built.

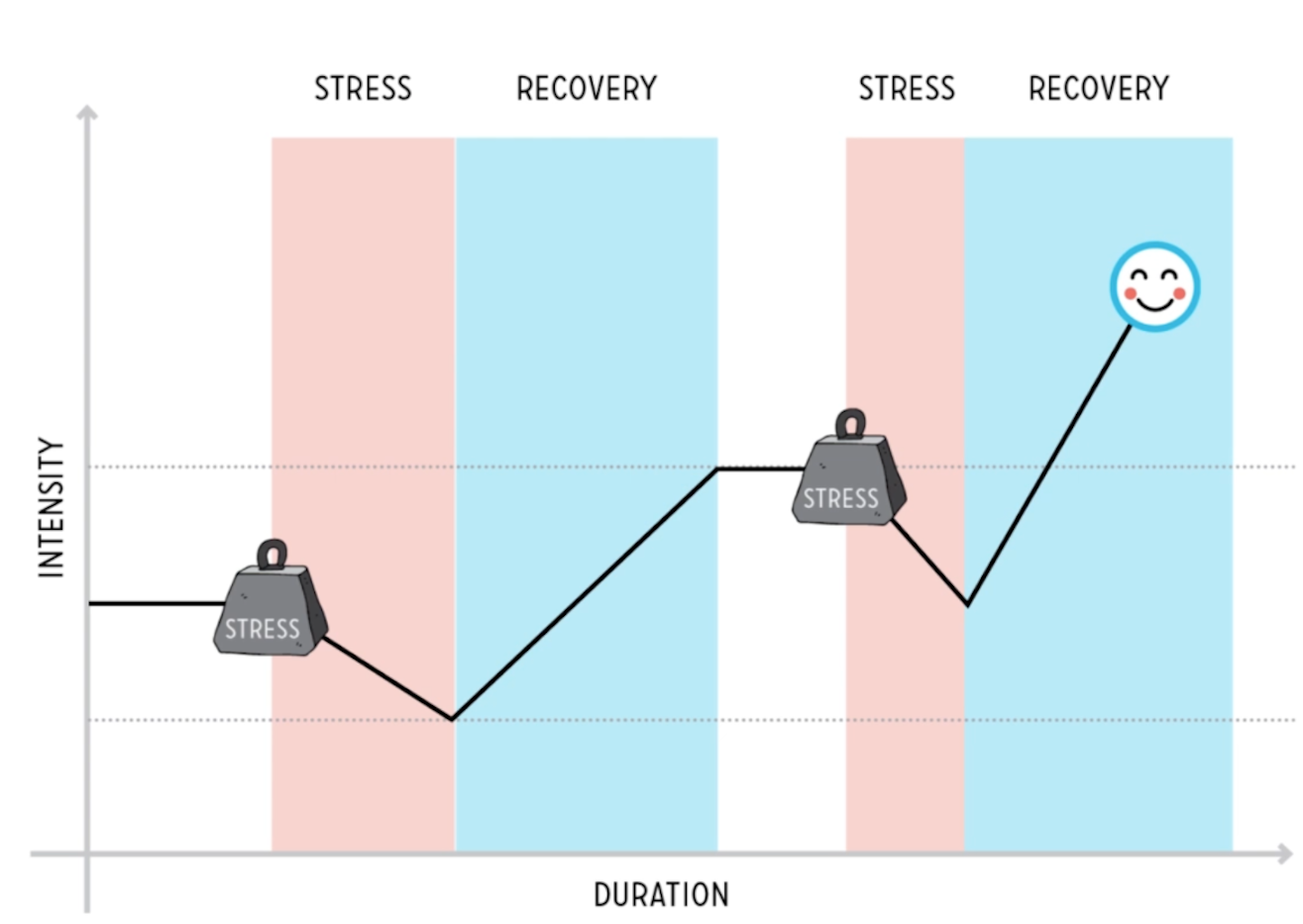

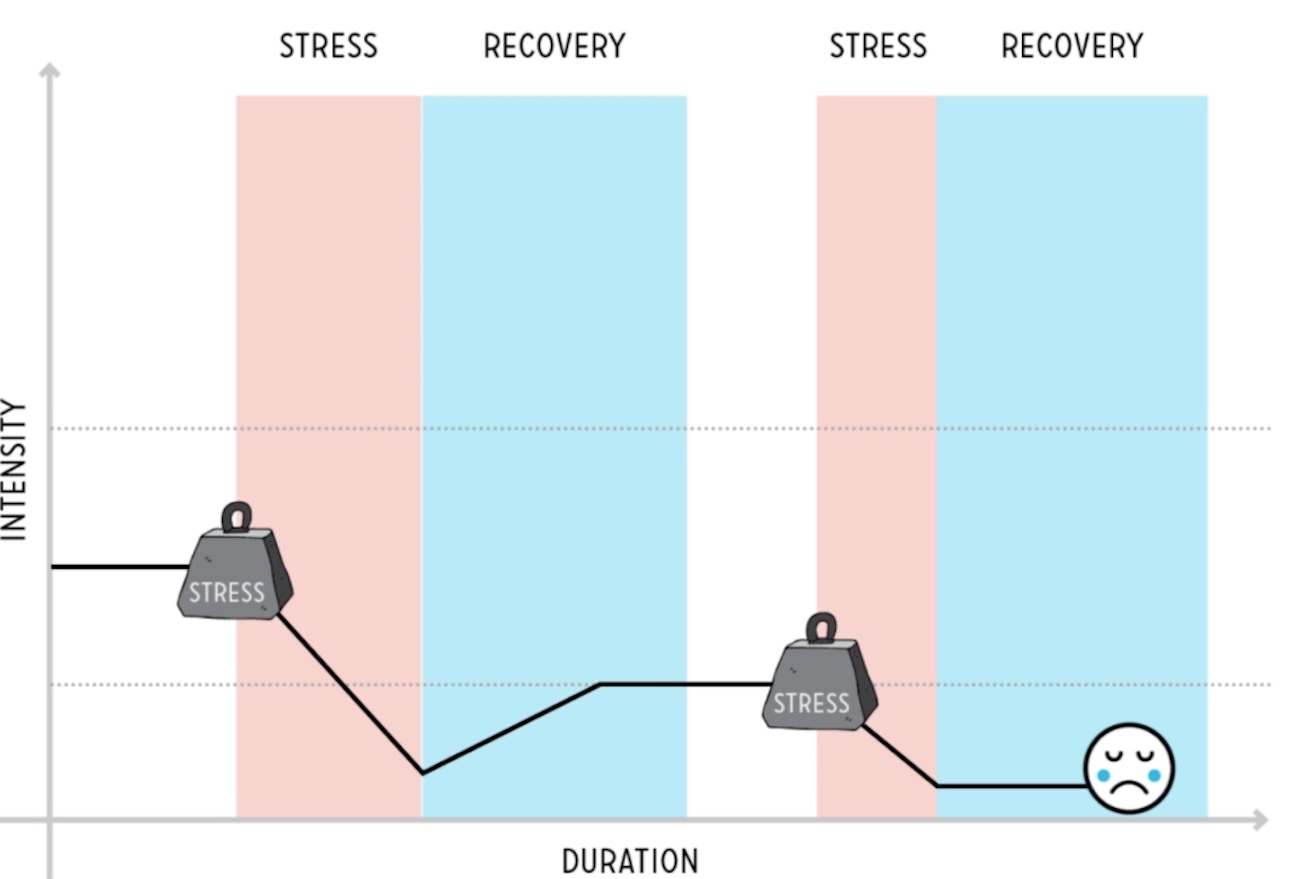

Strength is built during purposeful recovery.

When we recover and adapt well, stress makes us better.

When we don’t recover effectively, stress breaks us down.

Inadequate recovery = less strength and more fatigue.

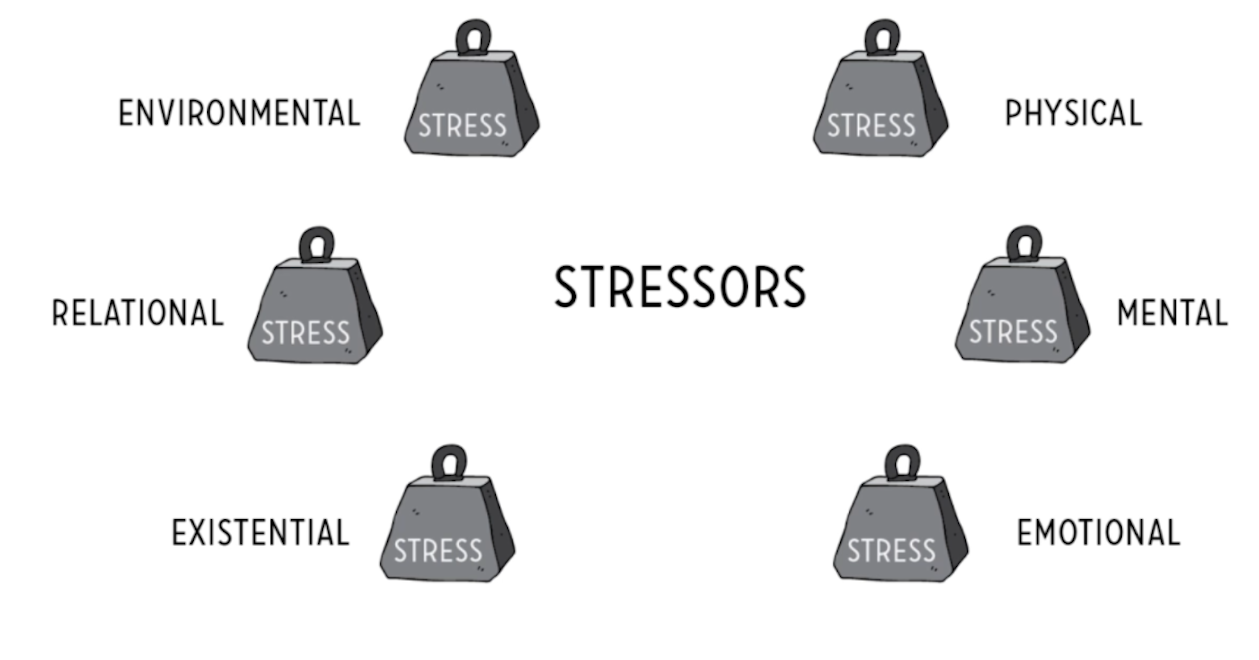

Workouts aren’t the only cause for needing more recovery.

Stress comes in many forms, from all dimensions of deep health.

Stressors can be external and physically felt.

Stressors can also be more internal and purely perceived or imagined.

Both types invoke the some real, physical stress responses. And, all stress is cumulative.

All stressors combined together create your experience of your “total allostatic load”.

Regardless of the source of stress, all stressors act on the same central nervous system that creates your experience of stress and fatigue or recovery and vitality.

No matter the source of stress, you’ll feel it in your body.

For an even clearer picture of your state of recovery, pay attention to all dimensions of deep health.

For example,

- How is your work stress and home stress?

- How many hours per night are you sleeping?

- How is your quality of sleep?

- How strong have you felt in training sessions recently?

- How are your relationships and emotional health?

For optimal whole-body recovery and performance, take a whole-life assessment of your state of recovery and what your body needs most to reach your goals for the long-term.